Identify the Clogs in Your Leadership Pipeline to Improve Your Organization’s DEI Strategy

As greater numbers of organizations seek to include more ethnically and culturally diverse people in their workforces, it becomes increasingly important to address differences in representation among the various levels of staff and leadership. In my previous article, I shared about the importance of retaining staff from underrepresented communities and looking for “leaks” in the company. Today, we will examine the problem of “clogs” in the leadership pipeline that prevents some employees from moving up in an organization.

Why Representation in Leadership Matters

According to Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business, companies that have more diverse senior leadership see benefits for workers of all ranks. “Research shows that there can be many positive benefits to minority followers if there are minorities in leadership positions,”[1] writes psychologist and assistant professor Nicholas Salter. Not only do minority followers feel empowered by having minority leaders to look up to, they feel understood and supported, and are given confidence that they could also become a leader someday.

The “Clog”

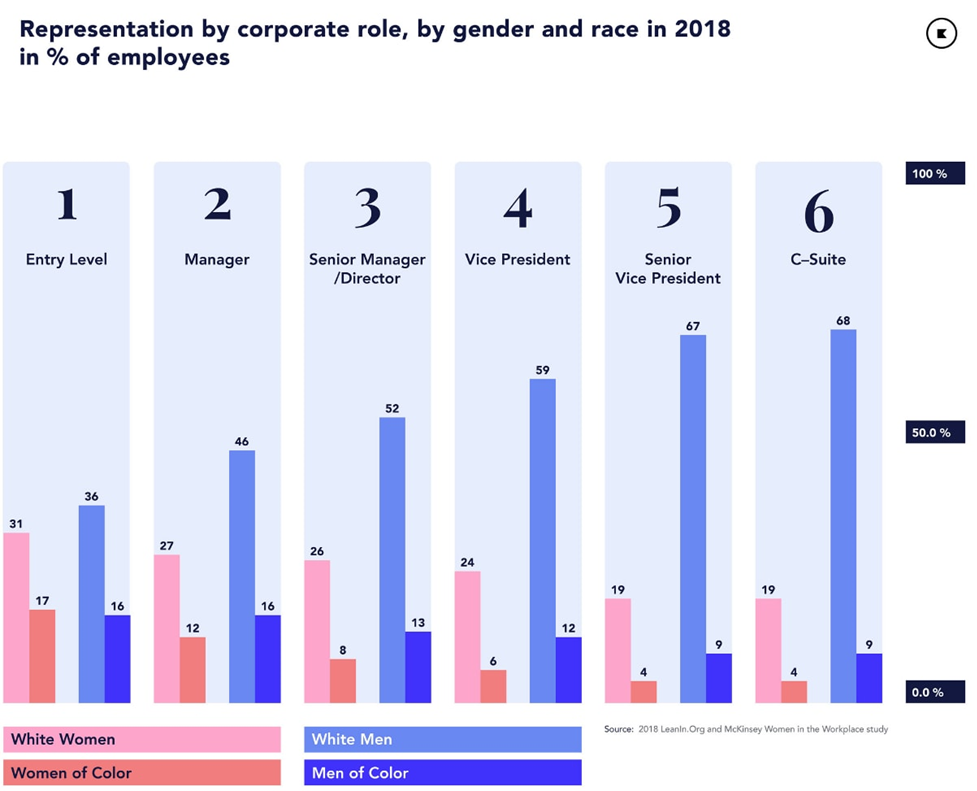

While it is evident that diverse representation in leadership is beneficial for organizations, numbers show that right now it isn’t happening much. Most companies face what I call a “clog” in the leadership pipeline. Somewhere around Senior Manager, Vice President and Senior Vice President, underrepresented talent stops getting promoted. Those who make it to C-Suite level are rare.

The graph below, by LeanIn.org and McKinsey Women in the Workplace study, illustrates it clearly. They studied more than 460 companies employing 19.6 million people. At entry-level positions, 36% are white men, 31% are white women, 17% are women of color, and 16% are men of color. White men represent larger and larger proportions as the positions move up the ranks and at the C-Suite level, the disparity is gaping. Within top leadership positions, a whopping 68% of them are held by white men, followed by 19% of white women, 9% are men of color, and women of color are the least represented at a mere 4%.[2]

According to Harvard Business Review’s article, Toward a Racially Just Workplace, “Just 8% of managers and 3.8% of CEOs are Black. [And] a mere 1.9% of tech executives and 5.3% of tech professionals are African-American.”[3] Multiple studies have shown that people of color who do make it into leadership positions have to manage their careers more strategically, prove greater competence before winning promotions, are disproportionately given “glass cliff” assignments where risks of failure are greater, and carry the burden of feeling isolated while also being expected to be “cultural ambassadors.”

In Canada, Ryerson University’s Diversity Institute studied Canadian board diversity and discovered that Black leaders are nearly non-existent on Canadian boards.[4] DiversityLeads 2020, supported by TD Bank Group analyzed the representation of “women, Black people, and other racialized persons among 9,843 individuals on the boards of directors across sectors in eight cities: Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary, Halifax, Hamilton, London, and Ottawa.” What they found was disheartening: only 0.8% of corporate board members in the study were Black. That’s 13 Black leaders among 1639 corporate board members. Commenting on the results of this study, founder and academic director of the Diversity Institute, Wendy Cukier, observes, “When we look at differences between sectors and within sectors, it’s pretty clear that the issue is not the pool or lack of available talent, but policies and processes around board recruitment.” There is obviously something preventing diverse talent from advancing up the leadership pipeline.

Why the “Clog” Exists

The reasons behind why there are so few minorities in senior leadership are varied and too broad for this article to cover extensively. However, the NCBI has a research paper that covers four studies which offers one possible explanation. In Think Leader, Think White? Capturing and Weakening an Implicit Pro-White Leadership Bias, authors Seval Gündemir, Astrid C. Homan, Carsten K. W. de Dreu, and Mark van Vugt remark, “We conjecture that a major cause of the underrepresentation of ethnic minorities in leadership positions in the Western world is that this group does not fit the predominant ‘image’ or prototype of a leader.”[5]

It is largely unconscious, but there is a bias toward choosing White people for senior leadership roles because that is the image most readily associated with what a leader looks like. The authors continue, “Across four studies, we uncover that leadership roles are more strongly associated–automatically and largely unconsciously–with White-majority group members than with ethnic minorities, and we expose the association between universal leadership prototypes with racio-ethnic categories (i.e., White-majority versus ethnic minority) in the Western world.”

It’s like a self-feeding cycle. The more White leadership there is, the more people associate White-majority with leadership, which in turn, results in more White people being given leadership positions. To interrupt this cycle and clear the “clog” takes intention and courage – beginning with White leaders themselves.

A Real-Life Example

In my own career, I have experienced the phenomenon of a “clog” in the leadership pipeline. In one of my first meetings with the CFO at Apple, I walked into the room and noticed it was all White males. I was the only Asian person at the meeting. There were no women and no other people of color. The positions represented at that meeting were senior level, ranging from Director to several VPs, to the CFO.

Back with my own team, I looked around the room and saw a vastly different picture. Out of our team of 100 people, 50% of us were people of color. There were a Black manager and a Latina director. The diversity of our entry-level to manager level team accurately reflected the diversity of our community and surrounding area. It was obvious that the talent pool was diverse, why then was that diversity lost the higher up the leadership ranks we went?

The challenge, then, for companies truly serious about broadening diversity throughout their organization, is not merely to hire and retain underrepresented talent. It is imperative to identify where the “clog” is and make changes to facilitate career advancements so that senior leadership positions are occupied with more representative talent. In the words of Nicholas Salter, “When minorities are represented in leadership, minority followers flourish – and so does everyone else.”

In future articles, I will explore four ways organizations can retain more of their underrepresented talent. Follow me on LinkedIn or subscribe to my email list to receive updates on my new articles.

Do you notice a “clog”

in your company or a company you have worked for? I’d love to hear your

experiences and stories.

[1] Salter, Nicholas, The Importance of Minority Leader Representation, The Ohio State University Fisher College of Business.

[2] Mehl, Bernhard, Study: Diversity in the Workplace 2020, Kisi.

[3] Roberts, Laura Morgan and Mayo, Anthony J., Toward a Racially Just Workplace, Harvard Business Review.

[4] Diversity Institute at Ryerson University, Black leaders are nearly non-existent on Canadian boards according to Ryerson’s Diversity Institute’s new study of Canadian board diversity, Cision Canada

[5] Gündemir, Seval, Homan, Astrid C., de Dreu, Carsten K. W., and van Vugt, Mark, Think Leader, Think White? Capturing and Weakening an Implicit Pro-White Leadership Bias, National Center for Biotechnology Information.

This article is part of a series of articles on the importance of retention in DEI. Other articles in this series include:

[…] and planning. In my previous articles, we examined how retaining underrepresented talent as well as identifying where minority staff aren’t given promotions in your organization are keys to fostering a diverse workplace. However, if you really want the diversity within your […]